Lessons Learnt on Refactoring Without Breaking

May 25, 2025

Tags: stats, quantile, rank, sublinear

December 31, 2024

Sorted observations stored in an array. Assuming 1-based index, the observation at rank r is at the index r.

Given n observations, finding which value is at rank r is trivially easy: if we store and sort the observations, the rank r will be at index r.

But when n gets really large, it is unfeasible to store or sort all the observations.

Greenwald and Khanna developed a data structure that solves this but with a trade off: we can answer which value is at rank r within certain error.

For the entire post I will talk about ranks. To deal with quantiles it is just a matter of computing its equivalent rank r \leftarrow q n.

It is called an q-quantile \epsilon-approximation summary.

I coded it, it didn’t work and after a week on this I realized that the original work of Greenwald an Khanna may have a few imprecisions.

This post describes how I rethinked the data structure from scratch, where I found the mentioned imprecisions and how I got a working implementation.

TL;DR -> python implementation in cryptonita

memcpy/memmove: overlap, words and alignment

Tags: memory, memcpy, copy, bytes, xoz

September 21, 2024

How do memcpy/memmove work?

I ended asking that question a few days ago while I was implementing the copy between sections of a file for the xoz library.

memcpy and memmove deal with memory, not with files, but I imagined that I could borrow some ideas anyways.

And I did.

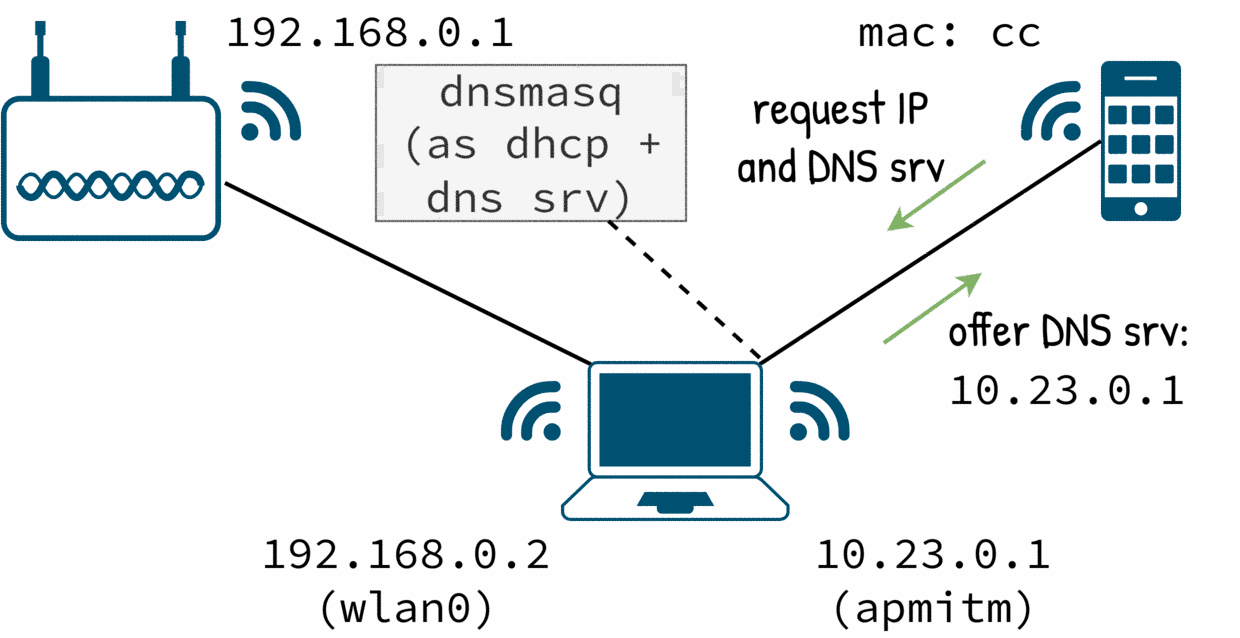

Tags: hostapd, dnsmasq, iptables, route, ap, wifi, mitm

October 20, 2023

I was curious about what a phone does behind the scene when it has a wifi connection. In this post I will go step by step on how to turn a wifi card into an access point and how to setup DHCP, DNS, routing and firewall rules to make a computer into a man in the middle box.

There are no hacks, spoofing or poisoning. I will go just through the happy case when I control the target device. Despite of this, it was a interesting problem to solve.

And when I made the mitm box work and I was celebrating, a careful inspection to the traffic shown a few surprises.

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, hash, extension

April 9, 2023

In the previous post we reviewed why and how an extension length attack is possible on some hash function and how we can use it to break a prefix-keyed MAC.

Long story short: when the full internal state of the hashing is exposed, an extension attack is possibly.

So hash functions that don’t expose their internal state are okay, right?

Yes in general but the devil is in the details…

SHA-224 does not expose its full state and it is one of those “safe” hash functions (sometimes it is found in the literature as such) but…

In this quick post we will see why SHA-224 is vulnerable to length extension attack even if its internal state is not fully exposed.

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, hash, extension

April 5, 2023

How can we know if a message is authentic or not?

A trusted party with access to a private key k can compute an authentication code or MAC.

Compute the message authentication code (MAC) doing H(k ∥ m).

In theory only who knows the secret key k can create and verify those, but no, this schema es broken.

This post covers matasano challenges from 28 to 30 so spoiler alert.

A keyed hash prefixes the message with the key k and computes a hash like SHA-1. The resulting hash is the MAC for the given message.

Then, someone that knows also k can verify if a message is authentic or not computing the MAC and comparing it with the one provided with the message.

If the computed hash matches the one provided, the message is authentic, otherwise it is not.

Unfortunately this prefix-keyed hash for MAC is broken.

Some very well known hash functions expose their internal states that allows an adversary to append data to the message and continue the hash computation and generate a new valid MAC.

Hence the name “length extension attack”.

Tags: hash, hashing, perf, performance, cython

March 30, 2023

There are a lot of hash algorithms for different use cases but tabulation hashing caught my attention years ago for its incredible simplicity and nice independence properties.

Fast and simple.

I will explore a cython implementation and see how fast really is.

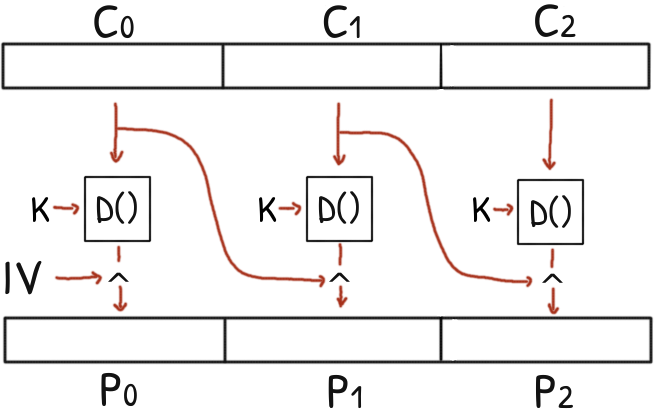

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, CBC

January 23, 2023

CBC requires an initialization vector (IV) that needs to be agreed by both encryption and decryption peers.

IV needs to be random so you may be get tempted and use the secret key as IV.

No, please don’t.

The IV is not required to be secret and there is a good reason for that: it can be recovered with a single chosen ciphertext attack.

Using \(IV = K\) means that the adversary can recover the secret key with a single message.

In this post I describe the attack in 3 simple diagrams.

Tags: python, dataframe, pandas

October 1, 2022

Let’s say that we want to compare two Pandas’ dataframes for unit testing.

One is the expected dataframe, crafted by us and it will be the source of truth for the test.

The other is the obtained dataframe that is the result of the experiment that we want to check.

Doing a naive comparison will not work: first we may want to tolerate some minor differences due computation imprecision; and second, and most important, we don’t want to know just if the dataframes are different or not

We want to know where are the differences.

Knowing exactly what is different makes the debugging much easier – trying to figure out which column in which row there is a different by hand is not fun.

August 27, 2022

We the pass of the years one keeps storing files, music in my case.

A few thousands.

But technology improved in this sense and new encoders exist that can compress (loosely) the same audio with the same quality but at a much smaller bit rate, and therefore, resulting in much smaller files.

Quick and dirty script follows!

Tags: python, pyte, terminal, optimization, performance

July 17, 2022

Few thoughts about Python code optimization and benchmarking for pyte and summarized here.

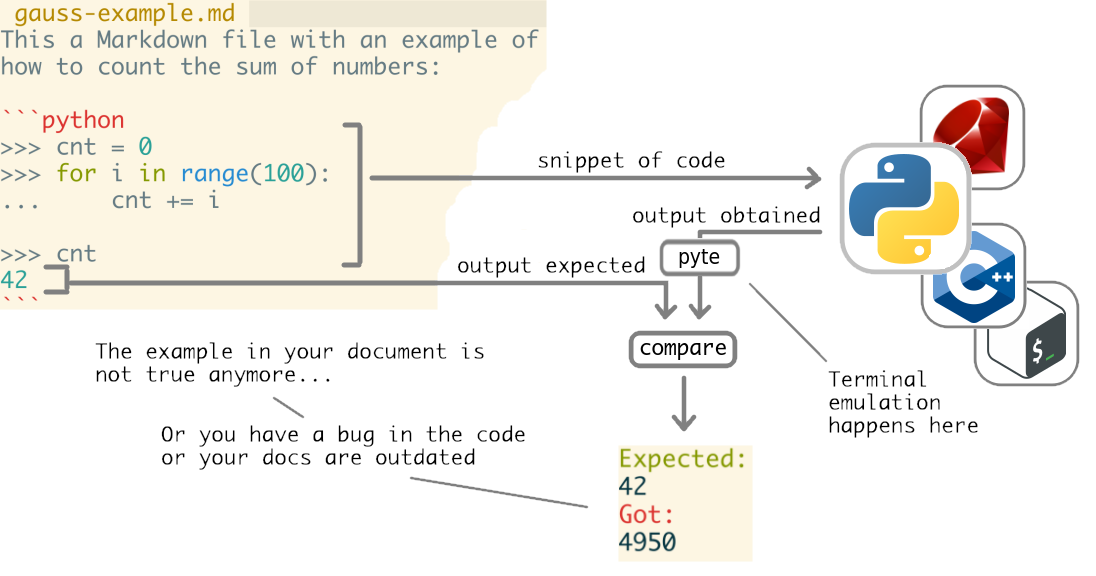

Tags: python, pyte, byexample, optimization, performance

July 15, 2022

byexample is a tool that reads snippets of code from your documentation, executes them and compares the obtained results with the expected ones, from your docs too.

If a mismatch happen we say that the example in your documentation failed that could mean one of two things:

Very useful for testing and keep your docs in sync!

But byexample does not really execute anything by itself. Having to code an interpreter for Ruby, Java, C++ and others would be insane.

Instead, byexample sends the snippets of code toa standard interpreter like IRB for Ruby or cling for C++.

Interpreting the output from they is not always trivial.

When a interpreter prints to the terminal, it may write special escape/control sequences, invisible to human eyes, but interpreted by the terminal.

That’s how IRB can tell your terminal to output something with reds and blues colors.

That’s how byexample’s +term=ansi is implemented.

byexample has no idea of what the hell those control sequences are and relays on a terminal emulator: pyte

byexample sends the snippets to the correct interpreter and its output feeds pyte.Screen. It is the plain text from the emulated terminal what byexample uses to compare with the expected output from the example.

But pyte may take seconds to process a single output so byexample never enabled it by default.

This post describes the why and how of the optimizations contributed to pyte to go from seconds to microseconds.

Tags: python, pyte, byexample, optimization, performance, tldr, tl;dr

July 14, 2022

This post describes to some level of detail all the performance boosts and speedups due the optimizations contributed to pyte and summarized here

For large geometries (240x800, 2400x8000), Screen.display runs orders of magnitud faster and consumes between 1.10 and 50.0 times less memory.

For smaller geometries the minimum improvement was of 2 times faster.

Stream.feed is now between 1.10 and 7.30 times faster and if Screen is tuned, the speedup is between 1.14 and 12.0.

For memory usage, Stream.feed is between 1.10 and 17.0 times lighter and up to 44.0 times lighter if Screen is tuned.

Screen.reset is between 1.10 and 1.50 slower but several cases improve if the Screen is tuned (but not all).

However there are a few regressions, most of them small but some up to 4 times.

At the moment of writing this post, the PR is still pending to review.

April 27, 2022

Previous posts: hierarchical organization

and resources distribution

In the previous post we saw that we cannot enable a controller or add a process to a cgroup freely. That would make the implementation of each controller harder.

In v2 the hierarchy is subject to the no internal process constraint that ensures that a controller will have all the processes in leaves of its domain tree.

This is the last of a 3-post series about cgroup and certainly, this no internal process constraint was the hardest to understand.

Tags: linux, kernel, cgroup, fork bomb

April 24, 2022

Previous post: hierarchical organization

Next coming post: no internal process constraint

A system has hundreds of resources that process may use (and exhaust!): controlling them it is not trivial and requires a precise intervention by part of the kernel.

We’ll use the simplest resource to understand: the amount of process ids or pids.

While CPU and memory are the most common resources that can be exhausted, the process id space is not infinite: it is an integer typically in the range of 1 to \(2^{16}\).

A malicious or really-bugged program can trivially consume all the available pids spawning thousands of processes and threads long before other resource get exhausted. This the so called fork bomb.

Once you run out of pids, no other process can be started leaving the system unusable.

In this post we will explore the rules of resources distribution in a cgroup hierarchy and in particular how to avoid fork bombs to explode.

April 23, 2022

Control group or cgroup is a mechanism to distribute and enforce limits over the resources of the system.

It was introduced in Linux kernel around 2007 but its complexity leaded to inconsistent behaviour and hard adoption.

Fast forwarding 9 years, in kernel 4.5 a rewrite of cgroup revamp the idea, making it simpler and consistent.

This post focus in the organization of cgroups and it is the first of a 3-posts series about cgroup in its new v2 version.

In the next posts we will see how the resources are distributed among the cgroups and which constraints do we have.

Tags: python

March 6, 2022

The following snippet loads any Python module in the ./plugins/ folder.

This is the Python 3.x way to load code dynamically.

>>> def load_modules():

... dirnames = ["plugins/"]

... loaded = []

...

... # For each plugin folder, see which Python files are there

... # and load them

... for importer, name, is_pkg in pkgutil.iter_modules(dirnames):

...

... # Find and load the Python module

... spec = importer.find_spec(name)

... module = importlib.util.module_from_spec(spec)

... spec.loader.exec_module(module)

... loaded.append(module)

...

... # Add the loaded module to sys.module so it can be

... # found by pickle

... sys.modules[name] = module

...

... return loaded

The loaded modules work as any other Python module. In a plugin system you typically will lookup for a specific function or a class that will serve as entry point or hooks for the plugin.

For example, in byexample the plugins must define classes that inherit from ExampleFinder, ExampleParser, ExampleRunner or Concern. These extend byexample functionality to find, parse and run examples in different languages and hook –via Concern– most of the execution logic.

Imagine now that one of the plugins implements a function exec_bg that needs to be executed in background, in a separated Python process.

We could do something like:

>>> loaded = load_modules() # loading the plugins

>>> mod = loaded[0] # pick the first, this is just an example

>>> target = getattr(mod, 'exec_bg') # lookup plugin's exec_bg function

>>> import multiprocessing

>>> proc = multiprocessing.Process(target=target)

>>> proc.start() # run exec_bg in a separated process

>>> proc.join()

This is plain simple use of multiprocessing…. and it will not work.

Well, it will work in Linux but not in MacOS or Windows.

In this post I will show why it will not work for dynamically loaded code (like from a plugin) and how to fix it.

Tags: kernel, file system, fuse

February 7, 2022

Yeup, why not implement the classic Tower of Hanoi using folders as the towers and files as the discs?

Using FUSE we can implement a file system that can enforce the rules of the puzzle.

Sounds fun?

Tags: docker

February 1, 2022

The file system of a docker container is ephemeral: it will disappear as soon as the container is destroyed.

To prevent data losses you can mount a folder of the host into the container that will survive the destroy of the container.

But it is not uncommon to find issues with the ownership and permissions of the shared files.

The file system of the host represents who is the owner of each file with an user and a group numbers.

Plain numbers.

Humans, on the other hand, think in terms of user names: “this is the file of Alice; this other is of Bob”.

The mapping between the numbers that the file system uses and the names that the humans understand is stored in /etc/passwd and /etc/groups.

And here we have a problem.

These two files, /etc/passwd and /etc/groups, live in the host’s file system and they are used to map the files’ numbers to names when you are seeing the files from the host.

When you enter into the docker container (or run a command inside), the shared files, mounted with -v, will have the same file numbers.

But, an here is the twist, inside the container you will be using for the mapping the /etc/passwd and /etc/groups files of the container and not of the host.

Same file numbers, different mappings.

Tags: pandas, julia, categorical, ordinal, parquet, statistics, seaborn

November 13, 2021

Histogram of TTL observed: the peaks indicate the different operative systems and their relative position respect the expected positions estimate the mean distance between the hosts and the scanner in hop count.

In the Multiprobes Analysis, we explored the statistics of the hosts and the communication to them.

This is a follow up to keep exploring the data:

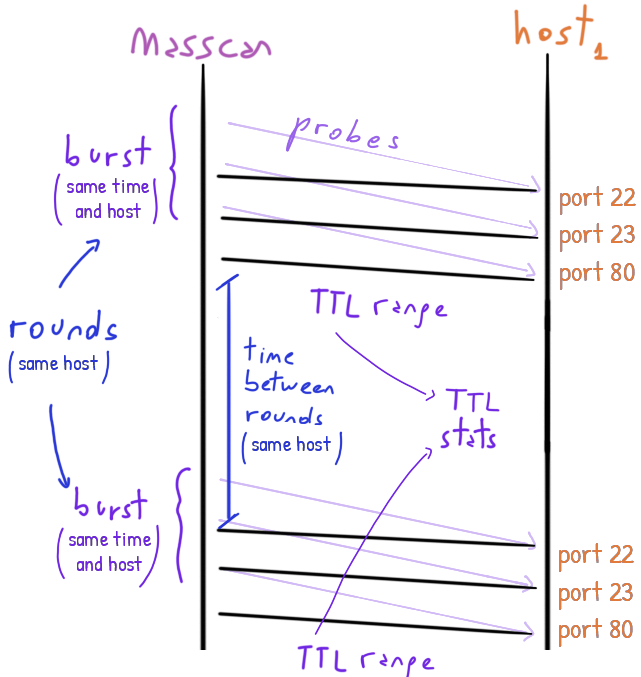

Tags: pandas, julia, statistics, seaborn

November 13, 2021

In the post about Hop-Stability we analyzed the TTL of the responses from all the scanned hosts.

In particular we used the TTL range: the difference between the smallest and the greatest TTL seen per host.

Histogram of TTL range between rounds of scans to the same host showing how much stable the routes are.

With a range of 0 or very close we claimed that the route to the host was stable; with range larger than 7 we said the contrary.

The analysis shown that only 0.39998% of 43056567 unique hosts had unstable routes.

However the analysis was only using a few statistics, when we plot the histogram of TTL ranges we see much more mysteries to solve.

Tags: pandas, julia, statistics, seaborn

October 16, 2021

masscan tracks the time to live of each packet coming from the host under scan.

Yes and no: they should not but some network devices will mangle the packets as they want, including setting arbitrary TTLs.

See the observations done in the TTL Boost post.

These time to live (TTL) are numbers between 0 and 255 set by the host. In its journey, the packet goes through different routers that each decrements by one the TTL.

Once a packet has a TTL of zero, the router will discard it.

Assuming that the packet goes straight-forward to us. If there are loops in the routing systems, the packet will loop between the devices going nowhere.

That’s the point of the TTL: to catch and drop packets looping around.

Of course the host set the TTL to some reasonable high number so the packet should reach to its destination (us) before reaching to zero.

We cannot know exactly which route/s the packets taken but we can count for how many hops they went through: any change in the hop-count and we will get different TTLs and that’s evidence that they taken different routes.

The inverse is not true: a constant hop-count does not imply that the route taken is the same, only the route/s have the same hops.

In this post I will continue exploring how much a route is stable in terms of hop-counts.

Tags: pandas, julia, categorical, ordinal, parquet, statistics, seaborn

September 19, 2021

To my surprise the dataset preprocessed in my previous post has duplicated entries. These are scans to the same host and port but with a different timestamp.

Histogram of the interval between probes to the same host-port in seconds.

Questions like “which open port is more likely” will biased because the same host-port may be counted more than once.

On the other hand, this opens new questions:

The second surprise was that even working with small samples (around 100MB), Pandas/Dask has serious performance problems:

groupby take forever.Goodbye Pandas, hello Julia?

Tags: pandas, reset_index, json, categorical, parquet

September 10, 2021

The dataset is a survey or port scan of the whole IPv4 range made with masscan.

The dataset however is much smaller than the expected mostly because most of the hosts didn’t response and/or they had all the scanned ports closed.

Only open ports were registered.

More over, of the 65536 available ports only a few were scanned and only for the TCP protocol.

Even with such reduced scope the dataset occupies around 9 GB.

This post is a walk-through for loading and preprocessing it.

Tags: android, root, privilege, priv-esc, escalation, dirty-cow

August 22, 2021

I’ve recently got a quite old Android phone to play with. I guess the first thing to do is getting root, don’t you think?

Tags: Python

August 14, 2021

When defining a Python function you can define the default value of its parameters.

The defaults are evaluated once and bound to the function’s signature.

That means that mutable defaults are a bad idea: if you modify them in a call, the modification will persist cross calls because for Python its is the same object.

>>> def foo(a, b='x', c=[]):

... b += '!'

... c += [2]

... print(f"a={a} b={b} c={c}")

>>> foo(1) # uses the default list

a=1 b=x! c=[2]

>>> foo(1) # uses the *same* default list

a=1 b=x! c=[2, 2]

>>> foo(1, 'z', [3]) # uses another list

a=1 b=z! c=[3, 2]

>>> foo(1) # uses the *same* default list, again

a=1 b=x! c=[2, 2, 2]

A mutable default can be used as the function’s private state as an alternative to functional-traditional closures and object-oriented classes.

But in general a mutable default is most likely to be a bug.

Could Python have a way to prevent such thing? Or better, could Python have a way to restart or refresh the mutable defaults in each call?

This question raised up in the python-list. Let’s see how far we get.

July 12, 2021

SMT/SAT problems are in general undecidable: basically we cannot know if we can get even an answer. The search space is in general infinite.

But several concrete problems have a reduced space and may be tractable: while theoretical really hard, we can find a solution in a reasonable time.

Still, a solver may need some extra help to navigate across the search space.

A strategy is a guide that hopefully will lead to a solution (sat or unsat) in a reasonable time using a reasonable amount of resources.

It is quite an art and the concepts were around for more than 30 years.

This post is a quick overview of concepts like strategies, tactics, tacticals, merit order, cost functions, heuristic functions, goals, approximations, redundancy control, search strategies, probes and a few more.

Quite a heavy post I’m afraid.

Tags: Python

July 11, 2021

Python 3.6 introduced the so called f-strings: literal strings that support formatting from the variable in the local context.

Before 3.6 you would to do something like this:

>>> x = 11

>>> y = 22

>>> "x={x} y={y}".format(x=x, y=y)

'x=11 y=22'

But with the f-strings we can remove the bureaucratic call to format:

>>> f"x={x} y={y}"

'x=11 y=22'

A few days ago Yurichev posted: could we achieve a similar feature but without using the f-strings?.

Challenge accepted.

Tags: z3, smt, sat, solver, if ITE, bithack, performance

June 14, 2021

A branch is an expensive operation even in modern CPUs because the computer will know which of the paths is taken only in the latest stages of the CPU pipeline.

In the meantime, the CPU stalls.

Modern CPUs use branch prediction, speculative execution and instruction reordering to minimize the impact of a branch.

They do a good job but still a branch is potentially expensive so they are replaced by branchless variants.

Minimum check-elapsed time (y axis) per branch/branchless function (x axis).

If-Then-Else or ITE for short, are symbolic expression that denotes a value chosen from two possible values based on a condition. These are the symbolic branch.

Naturally we could rewrite a symbolic ITE with a symbolic branchless expression.

The question is: which is better for a solver like Z3? Which makes the SMT/SAT solver faster?

After two weeks working on this post I still don’t have an answer but at least I know some unknowns.

June 12, 2021

I’ve being writing for a long time. I’m far from being a good writer but having the consistency to write at least a blog post every month gave me more expressive power.

Being a non-English native speaker, that also put me in an uncomfortable position –out of the confort zone– but looking back, even with all my mistakes, I really improved.

I’m using a bunch of different technologies to assist me:

And while those have been incredible powerful, I hit the limitations of them in time to time.

This writeup is meant to brainstorm and design a new way to work.

Tags: seaborn, matplotlib, pandas, plotting, cheatsheet

June 5, 2021

Plotting data was always for me a weak point: it always took me a lot of time to make the plots and graphs, reading the documentation, googling how to do one particular tweak and things like that.

So I challenge myself: could I build a cheatsheet about plotting?

Yes, yes I could.

Seaborn is a very simple but powerful plotting library on top of matplotlib designed for statistical analysis.

Quick links: PDF (no bg), PDF (bg), SVG (no bg), SVG (bg) .

Tags: z3, smt, sat, solver, bitvec bithacks

May 26, 2021

Z3 has a few basic symbolic operation over bit vectors.

But some others are missing (or at least I couldn’t find them).

Cast bit vectors to change the vector width, like when you want to upcast or promote a uint8_t to uint16_t, is one of them.

Arbitrary bitwise operations is another one. Z3 provides the basic And, Or and Xor but arbitrary functions needs to be defined and applied by hand.

And about function definitions, Z3 does not have a simple way to define a function from a lookup table (LUT) or truth table.

A much tricker that I thought!

This post is a kind-of sequel of Verifying some Bithacks post and prequel of some future posts.

Tags: z3, smt, sat, solver, bitvec, verify bithacks

May 17, 2021

We are going to verify some of the bit twiddling hacks made and collected by Sean Eron Anderson and other authors.

This is the classical scenario to put on test your Z3 skills.

Tags: z3, smt, sat, solver, propositional logic, first order

May 9, 2021

Victor has been murdered!

There are strong evidences that point that Victor was murdered by a single person. The investigation led to three suspects: Art, Bob, and Carl.

But who is the murder?

Tags: z3, smt, sat, solver, integer linear optimization

May 2, 2021

A space company is planning the next 4 years. It has several projects, each one with its own budget requirement per year, but the company has a limited budget to invest.

Moreover, some projects depends on others to make them feasible and some projects cannot be done if other projects due unbreakable restrictions.

| Project | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | Depends | Not | Profit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cube-1 nano-sat | 1.1 | 2 | 12 | ||||

| 2 Cube-2 nano-sat | 2.5 | 2 | 12 | ||||

| 3 Infrared sat | 1 | 4.1 | on 6 | with 4 | 18 | ||

| 4 Colored img sat | 2 | 8 | with 3 | 15 | |||

| 5 Mars probe | 2 | 8 | 4.4 | on 1 & 2 | 12 | ||

| 6 Microwave tech | 4 | 2.3 | 2 | 1 |

Under an incredible amount of assumptions and good luck, what is the best strategy to maximize the profit?

Tags: z3, smt, sat, solver, linear optimization, blending

April 29, 2021

A whisky producer uses three kind of licor to make their whisky: \(A\), \(B\) and \(C\).

Three kind of whisky can be made using the licor in the following proportions:

| Whisky | Sales Price | Recipe |

|---|---|---|

| \(E\) | \(680\) | No less than 60% of \(A\), no more than 20% of \(C\) |

| \(F\) | \(570\) | No less than 15% of \(A\), no more than 80% of \(C\) |

| \(G\) | \(450\) | No more than 50% of \(C\) |

The producer has the following stock and price list from its licor supplier:

| Licor | Stock | Price |

|---|---|---|

| \(A\) | \(2000\) | \(700\) |

| \(B\) | \(2500\) | \(500\) |

| \(C\) | \(1200\) | \(400\) |

Note: the prices are in $ per liter and the stock are in liters.

The goal is to maximize the profit.

Tags: z3, smt, sat, solver, linear optimization

April 27, 2021

A small business sells two types of chocolate packs: A and B.

The pack A has 300 grams of bittersweet chocolate, 500 grams of chocolate with walnuts and 200 grams of white chocolate.

The pack B has 400 grams of bittersweet chocolate, 200 grams of chocolate with walnuts and 400 grams of white chocolate.

The pack A has a price of 120$ while the pack B has a price of 90$.

Let’s assume that this small business has for today 100 kilograms of bittersweet chocolate, 120 kilograms of chocolate with walnuts and 100 kilograms of while chocolate.

How many packs of A and B type should be packed to maximize the profits?

Tags: z3, smt, sat, solver, equivalence, congruence, equivalence, set

April 25, 2021

Assume that you know that \(a = b\), \(b = c\) and \(d = e\). What can you tell me about the claim \(a = c\) ? Is it true or false?

April 24, 2021

A quick summary of the top 3 typos that I found (or I wrote) in code that they were small but they had a deep impact on the functionality.

In fact, the three bugs could summarized as follows:

u.s.*.Do you want to see what is this about?

Tags: quiescent, performance

March 7, 2021

You are working in optimizing a piece of software to reduce the CPU cycles that it takes.

To compare your improvements, it is reasonable to measure the elapsed time before and after your change.

Unless you are using a simulator, it is impossible to run a program isolated from the rest and your measurements will be noisy.

If you want to take precise measurements you need a quiescent environment as much as possible.

Tags: timers, clocks, performance

February 27, 2021

You want to measure the time that it takes foo() to run so you do the following:

void experiment() {

uint64_t begin = now();

foo();

uint64_t end = now();

printf("Elapsed: %lu\n", end - begin);

}

The question is, what now() function you would use?

February 18, 2021

What does the following code?

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int x[5];

printf("%p\n", x);

printf("%p\n", x+1);

printf("%p\n", &x);

printf("%p\n", &x+1);

return 0;

}

Tags: necklace, lyndon, debruijn, string

February 15, 2021

What have in common a dense arrays for mapping numbers power of 2 to some objects, DNA sequencing and brute-forcing the lock pad of your neighbor?

Tags: reversing, exploiting, ARM, iasm, azeria-labs, egg, shellcode, PIC

February 4, 2021

It’s time to solve the last challenge of this 7 parts serie.

Tags: reversing, exploiting, ARM, iasm, azeria-labs, egg, shellcode, PIC

January 26, 2021

We have the same vulnerability than we have in stack4 but this time we will make our own egg/shellcode.

Tags: reversing, exploiting, ARM, iasm, azeria-labs, egg, shellcode

January 20, 2021

Fifth challenge with a small introduction to process continuation.

Tags: reversing, exploiting, ARM, iasm, azeria-labs, objdump

January 19, 2021

This time the goal is to make the program print the message "code flow successfully changed".

Tags: reversing, exploiting, ARM, iasm, azeria-labs

January 18, 2021

Another fast moving post about exploiting the third Arm challenge

Tags: reversing, exploiting, ARM, iasm, azeria-labs

January 17, 2021

This is going to be a fast moving post, directly to the details, about exploiting the second Arm challenge

Tags: reversing, exploiting, ARM, qemu, iasm, azeria-labs

January 14, 2021

This is the first of a serie of posts about exploiting 32 bits Arm binaries.

These challenges were taken from Azeria Labs.

January 9, 2021

I crossed with a series of Arm challenges by causality and I decided to give it a shoot.

But I have 0 knowledge about Arm so the disassembly of the binaries were too strange for me.

I stepped back to plan it better: my idea was to use GDB to debug small snippets of Arm code, learn about it before jumping into the challenges.

I setup a QEMU virtual machine running Rasbian in an Arm CPU.

With a GCC and GDB running there I started but the compile-load-debug cycle was too inflexible.

I could not use it to explore.

If I wanted to see the effect of a particular instruction I needed to write it in assembly, compile it and debug it.

And the time between the “what does X?” and the “X does this” was too large, reducing the momentum that you have when you explore something new.

Too tedious.

So I decided to shorten the cycle writing an interactive assembler.

January 4, 2021

There is no other way to learn something that playing with it.

Take assembly code, read it and predice what will do. Then test it.

Those mistakes, those mismatches between what you think and what it really is, those surprises are what move us forward into learning. Deeper.

In this post I will dig into Arm, assisted with an interactive assembler.

December 15, 2020

Quick how-to download and run a Raspbian Buster (ARM) emulating the vm with QEMU.

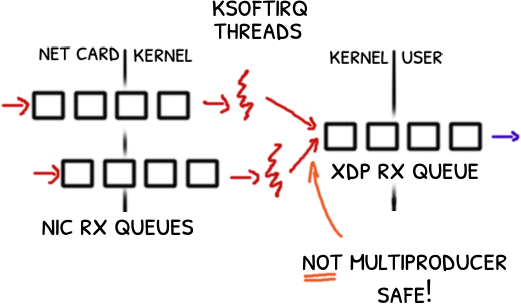

Tags: debugging, queue, lock free, kernel

November 29, 2020

Picture this: you’d been developing for six months a network sniffer using XDP, a kernel in-pass in Linux.

Six months and when you are about to release it, you find not one but three bugs that shake all your understanding of XDP.

A debugging race against the clock begins.

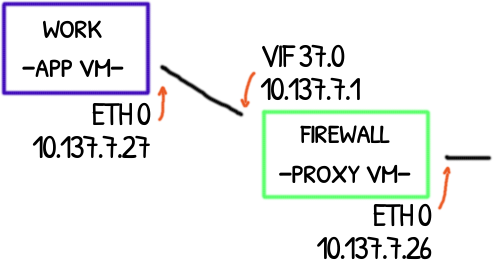

Tags: qubes, networking, ip, route, arp, firewall, iptables

November 19, 2020

Qubes OS has an interesting network system to isolate more-or-less trusted application virtual machines (App) from absolute untrusted network VMs (Net).

These last ones have the drivers required to handle ethernet and wifi cards that expose them to a potentially deathly bug lurking in the drivers.

An additional VM is put in the middle between App VMs and Net VMs. This absolute trusted proxy VM serves as a safe firewall (Proxy).

In this post will explore how these VMs connect and how the packets are forwarded up and down along this chain of VMs.

Tags: tldr, tl;dr, stylometric

November 12, 2020

A ghost writer is a person that writes a document, essay or paper but the work is presented by other person who claims to be the author.

Detecting deterring ghostwritten papers is an article written by a (ex)ghost writer and explains what happens behind the scene when a student pays for this dark service.

Would be possible to detect this in an automated way?

Given a set of documents, could we determine of they were written or not by the person or people who claim to be the authors?

This problem is known as authorship attribution and I will show a few papers that I read about this, in particular around the concept of stylometric, fingerprints that the real author leaves when he or she writes.

Tags: cryptography, cryptonita, vigenere, kasiski

October 11, 2020

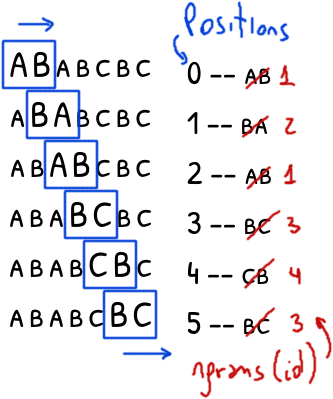

The tricky part of breaking the Vigenere cipher consists in finding the length of the key.

We discussed this in the breaking Vigenere post.

In that occasion we used the Hamming distance and the Index of Coincidence.

But another method existed much before the development of the IC around 1922.

In 1863, Kasiski published a method to guess the length of the secret key, method that we know today as the Kasiski test.

Let’s explore a \(O(\vert s \vert)\) solution with a worst case of \(O(\vert s \vert^2)\)

Tags: performance, debugging, rbspy, perf

September 13, 2020

executor.rb is a little program that starts and finishes other programs based on the needs of the system.

It is expected to have one and only one executor.rb process running with little overhead.

In one of the machines in the lab I found the opposite: two executor.rb instances and one of them running at top speed, consuming 100% of CPU.

For the rest, the system was working properly so one of the executor.rb was doing its job.

But what was the “twin evil” process doing with the CPU?

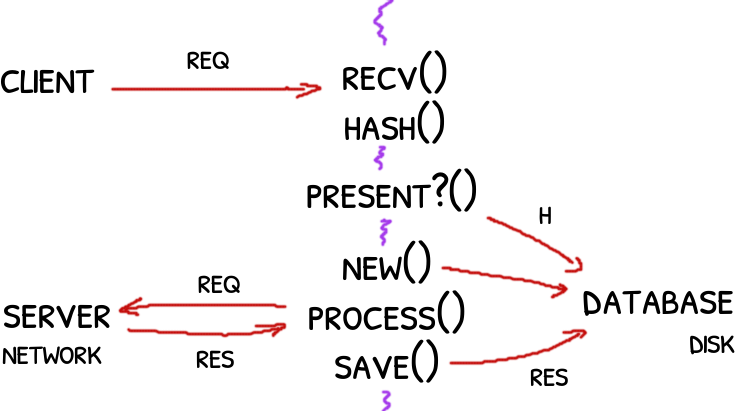

Tags: performance, architecture, queue, distributing

September 9, 2020

Original design: a little messy with IO mixed with CPU bounded code.

Original design: a little messy with IO mixed with CPU bounded code.

Could we design an architecture that allows us to have insight about the performance of the system?

When you spend nights debugging searching where is the bottleneck, it is when you blame the you of the past for a so opaque and slow architecture.

This is the proposal of a simple architecture that allows introspection and enables – too many times forgotten – basic optimizations.

Tags: performance, lock free, data structure, debugging

May 16, 2020

Debugging multithread code is hard and lock free algorithms is harder.

What cleaver tricks can we use?

Tags: performance, lock free, data structure, queue

April 28, 2020

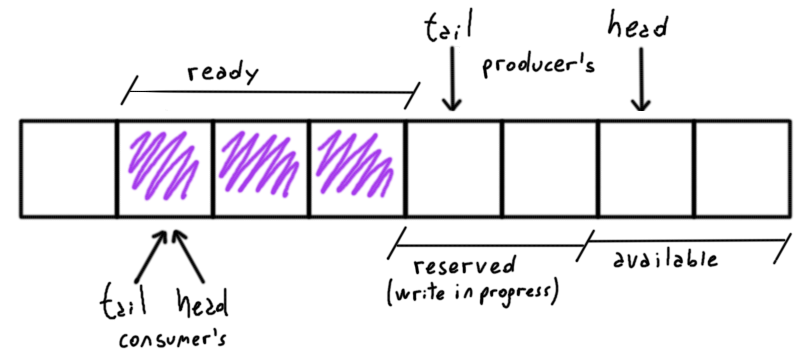

If implementing a lock-free queue for only one producer and consumer is tricky, adding more producers and consumers moves this to the next level.

This is the continuation of the lock-free single-producer single-consumer queue

Tags: identifier

April 19, 2020

What would be a nice identifier for the people in, let’s say, a database?

Tags: performance, lock free, data structure, queue

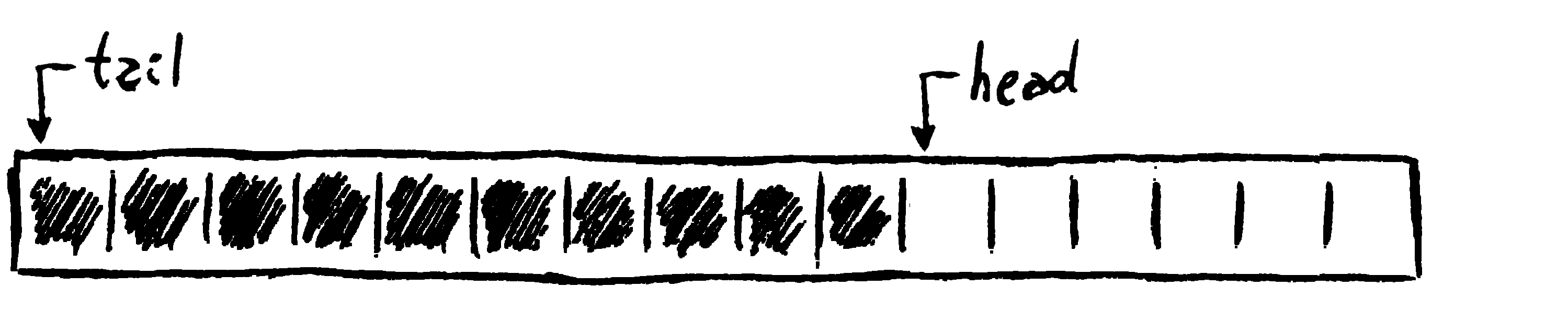

March 22, 2020

While implementing a bounded queue or ring buffer in a single-thread universe is relatively easy, doing the same when you have two threads, the implementation of a lock-free queue is more challenging.

In this first part will analyse and implement a lock-free single-producer single-consumer queue. A multi-producer multi-consumer queue is described in the second part.

Tags: reversing, performance, cache, CPU

February 15, 2020

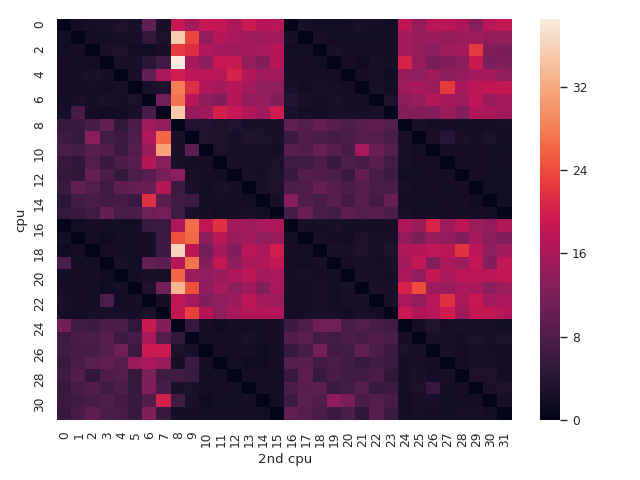

Most modern cpus see a single shared main memory seeing the same thing, eventually.

This post explores what is behind this “eventually” term.

Tags: reversing, IDA, performance, volatile

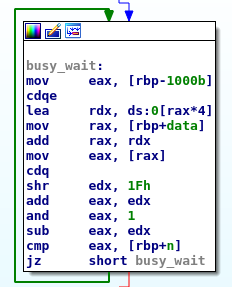

February 7, 2020

When two or more concurrent tasks perform non-atomic read/write operations over the same data we have a race condition and the system will be in an undefined state.

But what exactly does that suppose to mean? What is behind the generic undefined state?

Tags: eko, challenge, reversing, IDA

October 27, 2019

rpg is a buggy game where the player can attack to and defend from attacks of monsters.

Let’s see if we can know how it works.

Tags: algorithm, game, clocks, frame rating

October 23, 2019

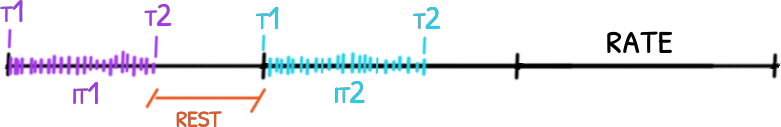

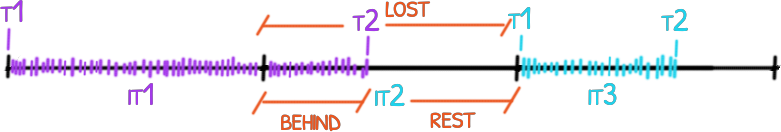

Same animation that last 1 second in a loop. From top to down, the first is an animation without any frame lost, the second had lost some frames but

Same animation that last 1 second in a loop. From top to down, the first is an animation without any frame lost, the second had lost some frames but draw() is still in sync, the last one lost the same amount of frames but draw() used its own notion of time an got out of sync. code

Tags: cryptography, index of coincidence

October 4, 2019

The concept of Index of Coincidence was introduced by William Friedman in 1922-1923 in the paper titled “The Index of Coincidence and its Applications in Cryptoanalysis” [1].

The Navy Department (US) worked in the following years on this topic coming, in 1955, with a paper titled “The Index of Coincidence” by Howard Campaigne [2].

However I found some confusing and misleading concepts in the modern literature.

This post is a summary of what I could understand from Howard’s work.

Tags: challenge, eko, hacking, python, bytecode

October 1, 2019

We start with a communication between two machines, encrypted with an unknown algorithm and the challenge is to break it.

As a hint we have the code that the client used to talk with the server.

Tags: challenge, eko, sql, hacking

September 29, 2019

Quick writeup of a SQL injection challenge.

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, CTR, counter, forgery

August 22, 2019

No much to explain: encryption does not offer any protection against forgery.

– Spoiler Alert! –

We saw this in the CBC Bitflipping post and we will see it again here but this time it will be the CTR encryption mode our victim.

Tags: scripting, string compression

August 4, 2019

The logs present several patterns that are repeated again and again; LZMA takes advantage of that and reaches very high compress ratios.

Doing a quick test, LZMA at the 6 level of compression, compressed a 2.5 GB log into 147 MB very tight binary blog. A ratio of 94.069%, not bad!

But could we get better results?

Tags: regex, automata, state machine, NFA, string

July 25, 2019

Before building complex state machine we need to learn the basics blocks.

When the solution to a problem can be seen as set of states with transitions from ones to others, modeling them as a nondeterministic finite automatas makes clear how the solution works and allows to spot deficiencies.

A regular expression is an example of this. As an introductory step let’s review how to turn a regex into a NFA.

Take at look of the source code in Github.

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, CTR, counter, forgery

May 8, 2019

A CTR-mode cipher turns a block cipher into a stream cipher.

With this, a ciphertext can be edited in place generating enough of the key stream, decrypting and re-encrypting the edited portion.

– Spoiler Alert! –

One can replace part of the plaintext, extend it or even reduce it.

But this beautiful property of a CTR mode (and any other stream cipher) is actually a booby-trap.

Tags: cryptography, cryptonita, affine, differential attack

March 20, 2019

A linear cipher like the Hill Cipher is vulnerable to a known plaintext attack: just resolve a set of linear equations and get the secret key.

An affine cipher is a little harder to break, however it could be vulnerable to a differential attack.

Tags: bash, scripting, security

March 15, 2019

Using a ssh-agent to handle our keys is handy.

When you need to access to different hosts jumping from one to another, forwarding the agent is much more secure than copying and pasting your keys around.

But if one host gets compromised it will expose your agent: even if the attacker will not get your secret keys he will be able to login into any system as you.

You cannot prevent this, but you can restrict this to reduce the splash damage.

Tags: cryptography, cryptonita

February 3, 2019

The Cape library offers a symmetric stream cipher implemented in cape_decrypt and cape_encrypt.

cape_hash is an unfortunately name for a cipher.

In addition, it offers another symmetric stream cipher, a slightly different of the first one, implemented in cape_hash.

In this write-up we are going to analyze the cape_hash stream cipher and see if we can break it.

Tags: cryptography, cryptonita, hill cipher

January 2, 2019

Given a matrix secret key \(K\) with shape \(n\textrm{x}n\), the Hill cipher splits the plaintext into blocks of length \(n\) and for each block, computes the ciphertext block doing a linear transformation in module \(m\)

$$ K p_i = c_i\quad(\textrm{mod } m)$$For decrypting, we apply the inverse of \(K\)

$$ p_i = [K]^{-1} c_i \quad(\textrm{mod } m)$$To make sense, the secret key \(K\) must be chosen such as its inverse exists in module \(m\).

Ready to break it?

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, MT19937, PRG

December 23, 2018

The Mersenne-Twister 19937 or just MT19937 is one of the most used pseudo random number generator with a quite large cycle length and with a nice random quality.

However it was not designed to be used for crypto.

– Spoiler Alert! –

But some folks may not know this…

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, CTR, counter nonce, PRG, chi-square, undistinguishable

December 4, 2018

The Counter mode, or just CTR mode, turns a block cipher into a stream cipher.

More specifically, it builds a pseudo random generator (PRG) from a block cipher and then generates a random string using the PRG to encrypt/decrypt the payload performing a simple xor.

The idea is to initialize the PRG with a different seed each time but if this does not happen, all the plaintexts will be encrypted with the same pseudo random key stream – totally insecure.

– Spoiler Alert! –

Ready to break it?

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, CBC, cipher block chaining, padding oracle

October 28, 2018

AES and other ciphers work on blocks; if the plaintext length is not multiple of the block size a padding is added.

If during the decryption the pad is checked and returns an error, we can use this to build a padding oracle: a function that will tell us if an encrypted plaintext has a valid pad or not.

It may not sound too much exiting but armed with this padding oracle we can break CBC one byte at time.

– Spoiler Alert! –

Ready? Go!

Tags: bash, shellshock, hacking

October 1, 2018

Despite of been 4 years old, Shellshock is still a very interesting topic to me not for the vulnerability itself but for the large ways to trigger it even in the most unexpected places.

Take the 4 characters () { and open the world.

Fragments found in the field.

Fragments found in the field.

Creativity and few hours reading man pages are all what you need.

Tags: circular buffer, data structure, performance

September 16, 2018

struct circular_buffer is a simple but quite efficient implementation of a circular buffer over a continuous and finite memory slice.

The name Ouroboros comes from the Ancient Greek and symbolize a snake eating its own tail – a convenient image for a circular buffer.

Source code can be found in the tiburoncin project. Enjoy it!

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, CBC, cipher block chaining, forgery, forge, bit flipping

July 3, 2018

CBC does not offer any protection against an active attacker.

Flipping some bits in a ciphertext block totally scrambles its plaintext but it has a very specific effect in the next plaintext block.

– Spoiler Alert! –

Without any message integrity, a CBC ciphertext can be patched to modify the plaintext at will.

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, ECB, forgery, forge

July 1, 2018

In this game we control partially a plaintext that is encrypted under ECB mode with a secret key.

This time the idea is not to reveal the key but to forge a plaintext.

– Spoiler Alert! –

Welcome to the ECB cut-and-paste challenge!

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, ECB

June 10, 2018

– Spoiler Alert! –

In the previous post we built an ECB/CBC oracle; now it’s time to take this to the next level and break ECB one byte at time.

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, ECB, CBC, oracle PKCS#7

June 9, 2018

In this post will review the Cipher Block Chaining mode (or CBC) and how we can build an ECB/CBC detection oracle to distinguish ECB from CBC using cryptonita

– Spoiler Alert! –

This will be the bases for breaking ECB in a later post.

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, ECB, electronic code block

May 20, 2018

– Spoiler Alert! –

Can you see the penguin?

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, vigenere

May 1, 2018

A plaintext was encrypted via a XOR with key of unknown bytes of length, repeating this key as much as needed to cover the full length of the plaintext.

This is also known as the Vigenere cipher.

It is 101 cipher, which it is easy to break in theory, but it has more than one challenge hidden to be resolve in the practice.

– Spoiler Alert! –

Shall we?

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, index coincidence

April 1, 2018

A cipher is semantically secure if given a randomly chosen key, its ciphertext cannot be distinguishable from a truly random string.

Detecting a ciphertext from a pool is enough to consider the cipher as not secure even of we can’t break it.

In the following pool of random strings one is actually a ciphertext that is the xor encryption of a plaintext using a single-byte key.

>>> from cryptonita import B, load_bytes # byexample: +timeout=10

>>> ciphertexts = list(load_bytes('./posts/matasano/assets/4.txt', encoding=16))

>>> methods = {}

– Spoiler Alert! –

This is obviously a poor and not secure encryption mechanism; let’s find the ciphertext then!

Tags: cryptography, matasano, cryptonita, repeating key

March 1, 2018

This is the first set of exercises for the Matasano Challenge (also known as the Cryptopals Challenge)

It starts from the very begin, really easy, but it goes up to more challenging exercises quickly.

– Spoiler Alert! –

Ready? Go!

Tags: wifi, container, hacking

April 16, 2017

HTTP Proxies blacklisting evil domains, firewalls blocking weird traffic and IDSs looking for someone that shouldn’t be there are reasonable and understandable policies for a corporate environment.

But when a friend opened his browser this week and went to google.com the things got odd.

The browser refused the connection warning him that the SSL certificate of the server wasn’t issue by google.com at all or signed by a trusted authority.

Tags: forensics

December 18, 2016

A friend of mine called me: a girl friend of him was hopeless trying to recover her thesis from a corrupted usb stick three days before her presentation.

She was working in her thesis for almost a year, saving all the progresses in that usb stick. But what she didn’t know was that an usb memory has a limited number of writes and with more writes eventually the file system gets corrupted.

This is the real story behind a forensics rally trying to recover her one year work.