Ouroboros - Circular Buffer

September 16, 2018

struct circular_buffer is a simple but quite efficient implementation of a circular buffer over a continuous and finite memory slice.

The name Ouroboros comes from the Ancient Greek and symbolize a snake eating its own tail – a convenient image for a circular buffer.

Source code can be found in the tiburoncin project. Enjoy it!

Playing with a Circular Buffer

You can run this code with cling and byexample

First, let’s load this module to play with it:

?: .L circular_buffer.c

?: #include "circular_buffer.h"

?: #include <string.h>

Now, let’s create a buffer of 16 bytes:

?: struct circular_buffer_t buf;

?: circular_buffer_init(&buf, 16);

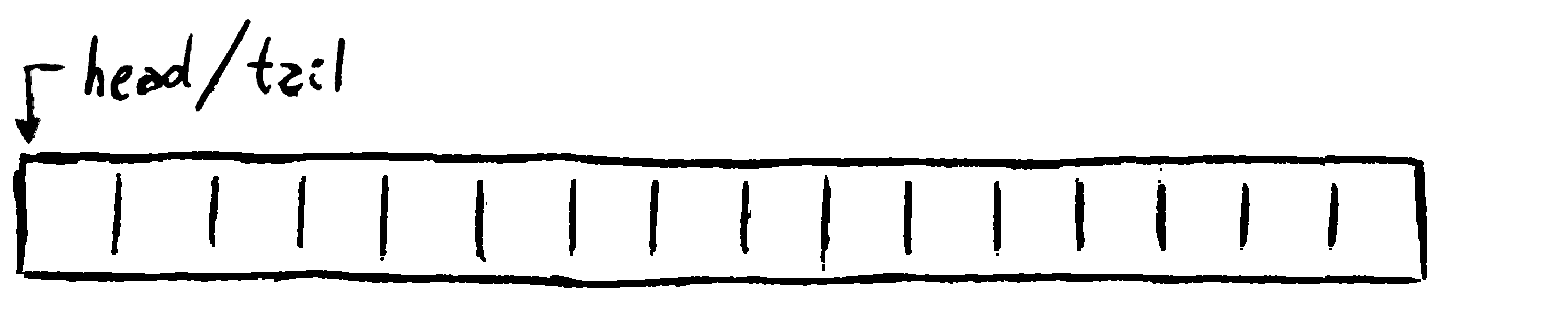

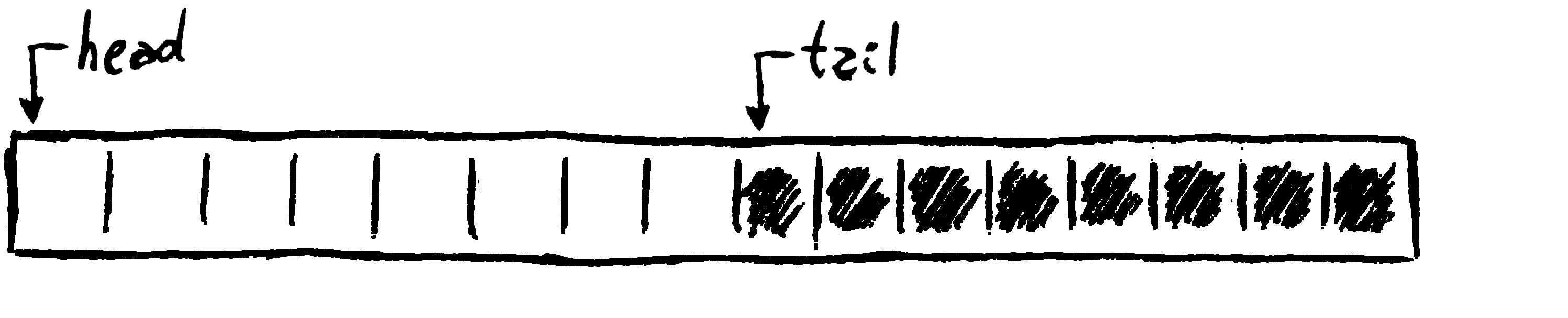

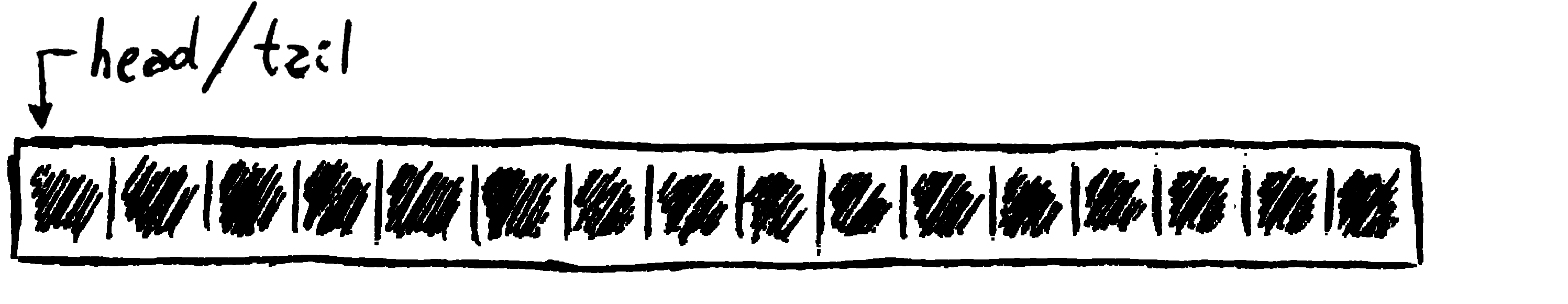

The circular buffer has 2 pointers, the head that mark the end of the data and the begin of the free space and the tail, which it is the opposite of the head.

At the begin, both pointers point to the same place, the free space has the size of the whole buffer and the ready space is empty:

?: (buf.head == buf.tail)

(bool) true

?: circular_buffer_get_free(&buf)

(unsigned long) 16

?: circular_buffer_get_ready(&buf)

(unsigned long) 0

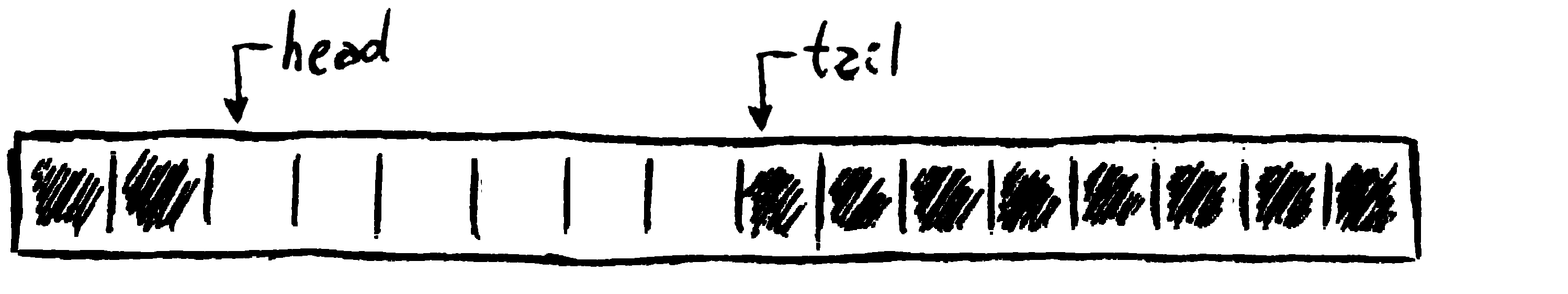

When more data is written in the buffer, the head pointer moves forward, the free space is reduced and the ready space is increased, all of them in the same proportion.

The implementation does not track how many bytes are written. It is up to the caller to write in the buffer from the buffer’s head and notify the circular buffer how many bytes wrote.

For example, if we write 10 bytes:

?: memcpy(&buf.buf[buf.head], "AABBCCDDEE", 10);

Then we must notify how many bytes were written updating the head pointer:

?: circular_buffer_advance_head(&buf, 10);

?: (buf.head > buf.tail)

(bool) true

?: circular_buffer_get_free(&buf)

(unsigned long) 6

?: circular_buffer_get_ready(&buf)

(unsigned long) 10

We can keep writing and reading from the buffer.

As we did with the write, once we read the data from the buffer’s tail we need to notify to the circular buffer that the data can be discarded.

?: memcpy(&buf.buf[buf.head], "FFGG", 4);

?: circular_buffer_advance_head(&buf, 4);

?: char read[8];

?: memcpy(read, &buf.buf[buf.tail], 8);

?: circular_buffer_advance_tail(&buf, 8);

?: read

(char [8]) "AABBCCDD"

How many bytes we can write is determined by how many free space the buffer has; how many bytes we can read is determined by how many ready space the buffer has.

It is up to the caller honor this.

?: (buf.head > buf.tail)

(bool) true

?: circular_buffer_get_free(&buf)

(unsigned long) 2

?: circular_buffer_get_ready(&buf)

(unsigned long) 6

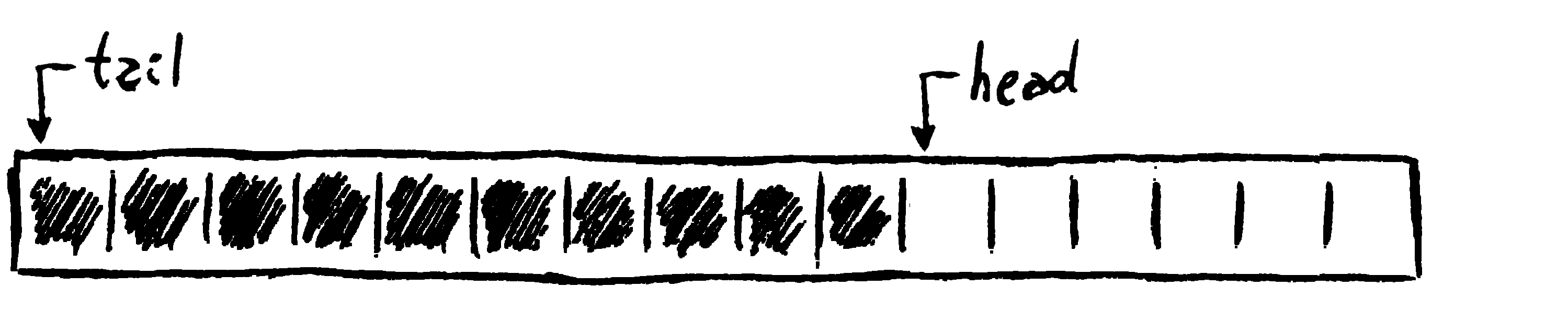

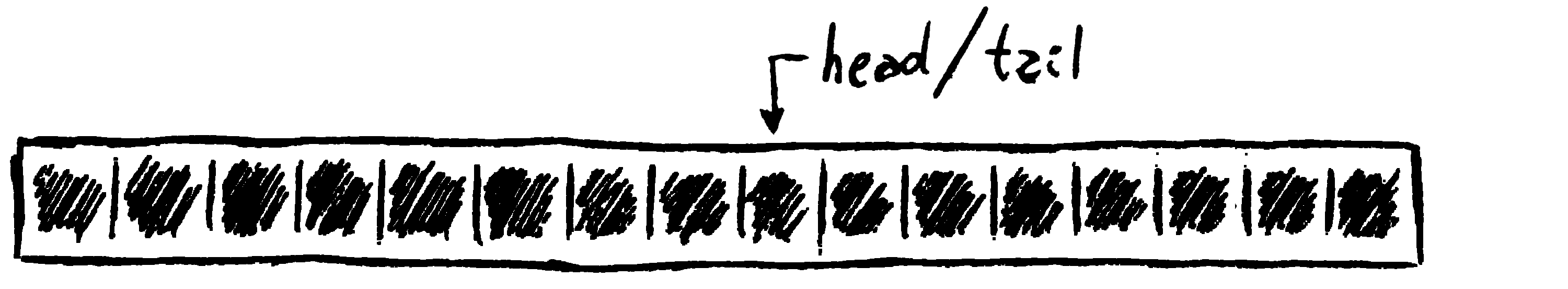

When the head pointer reaches the end of the buffer, the pointer is restarted and set back to the begin.

The free space is expanded from the head to the tail and the tail is in front of the head:

?: circular_buffer_advance_head(&buf, 2);

?: (buf.tail > buf.head)

(bool) true

?: circular_buffer_get_free(&buf)

(unsigned long) 8

?: circular_buffer_get_ready(&buf)

(unsigned long) 8

Contiguous reading and writing

If we keep writing (moving the head), the ready space will not increase because the circular buffer will always inform how many contiguous bytes are ready (for reading) or free (for writing).

The ready space is limited by the end of the buffer in this case:

?: circular_buffer_advance_head(&buf, 2);

?: (buf.tail > buf.head)

(bool) true

?: circular_buffer_get_free(&buf)

(unsigned long) 6

?: circular_buffer_get_ready(&buf)

(unsigned long) 8

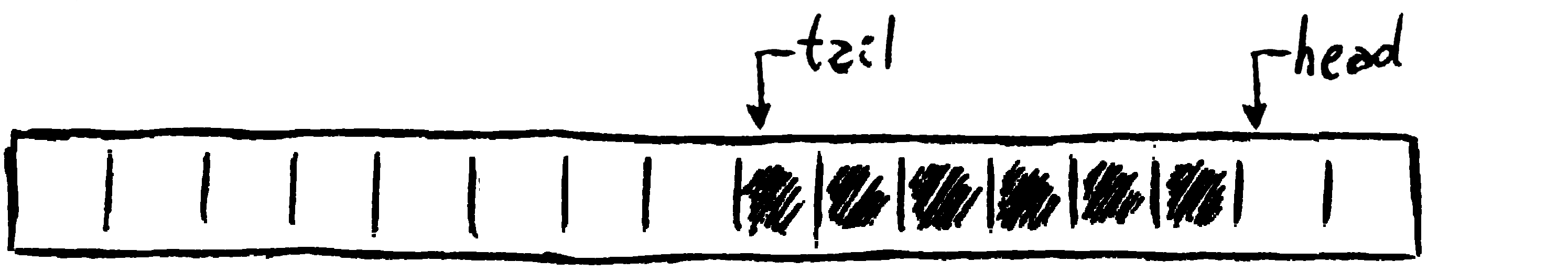

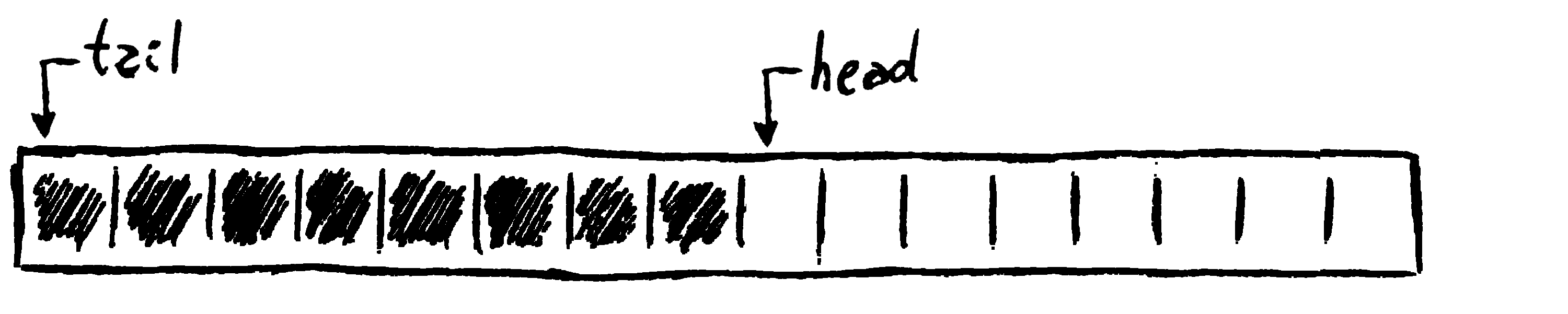

When the head bites the tail

The critical point happens when the head reaches the tail.

Now, this is exactly the same situation that happen at the begin, when the buffer was empty, but now it means that it is full.

To differentiate these two cases, internally there is a flag that tracks when the head is behind the tail:

?: circular_buffer_advance_head(&buf, 6);

?: (buf.tail >= buf.head)

(bool) true

?: circular_buffer_get_free(&buf)

(unsigned long) 0

?: circular_buffer_get_ready(&buf)

(unsigned long) 8

?: (buf.hbehind)

(bool) true

If we move the tail to the end of the buffer, the rest of the bytes written are ready to be consumed and the head is in front of the tail again:

?: circular_buffer_advance_tail(&buf, 8);

?: (buf.head >= buf.tail)

(bool) true

?: circular_buffer_get_free(&buf)

(unsigned long) 8

?: circular_buffer_get_ready(&buf)

(unsigned long) 8

?: (buf.hbehind)

(bool) false

If we move the head to the end we will reach again to the ambiguous cases but the hbehind variable tell us that the head is behind the tail again:

?: circular_buffer_advance_head(&buf, 8);

?: (buf.tail >= buf.head)

(bool) true

?: circular_buffer_get_free(&buf)

(unsigned long) 0

?: circular_buffer_get_ready(&buf)

(unsigned long) 16

?: (buf.hbehind)

(bool) true

Final bits

Finally, do not forget to destroy the buffer:

?: circular_buffer_destroy(&buf);

Related tags: circular buffer, data structure, performance